Sense and Sensibility

| Sense and Sensibility | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Author | Jane Austen |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novel |

| Publisher | Thomas Egerton, Military Library (Whitehall, London) |

| Publication date | 1811 |

| ISBN | N/A |

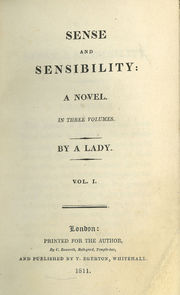

Sense and Sensibility is a novel by the English novelist Jane Austen. Published in 1811, it was Austen's first published novel, which she wrote under the pseudonym "A Lady".

The story revolves around Elinor and Marianne, two daughters of Mr. Dashwood by his second wife. They have a younger sister, Margaret, and an older half-brother named John. When their father dies, the family estate passes to John, and the Dashwood women are left in reduced circumstances. The novel follows the Dashwood sisters to their new home, a cottage on a distant relative's property, where they experience both romance and heartbreak. The contrast between the sisters' characters is eventually resolved as they each find love and lasting happiness. Through the events in the novel, Elinor and Marianne find a balance between sense (or pure logic) and sensibility (or pure emotion) in life and love.

The book has been adapted for film and television a number of times, including a 1981 serial for TV directed by Rodney Bennett; a 1995 movie adapted by Emma Thompson and directed by Ang Lee; a version in Tamil called Kandukondain Kandukondain released in 2000; and a 2008 TV series on BBC adapted by Andrew Davies and directed by John Alexander.

Contents |

Plot summary

When Mr. Dashwood dies, his estate - Norland Park - passes directly to John, his only son, and child of his first wife. Mrs. Dashwood, his second wife, and their daughters, Elinor, Marianne and Margaret, are left only a small income.

On his deathbed, Mr. Dashwood had asked John to promise to take care of his half-sisters but John's selfish and greedy wife, Fanny, soon persuades her weak-willed husband that he has no real financial obligation in the matter, and he gives the girls and their mother nothing. John and Fanny move into Norland immediately on the death of Mr Dashwood and take up their place as its new owners. The Dashwood women, now treated as rather unwelcome guests in what was their home, begin looking for another place to live - a difficult task because of their small income.

Fanny's brother, Edward Ferrars, a pleasant, unassuming, intelligent but reserved young man, comes to Norland for a visit. He and Elinor are clearly attracted to each other and Mrs. Dashwood cherishes hopes that they will marry. Fanny makes it clear that their mother, Mrs. Ferrars, a wealthy widow, wants her son to make a career for himself and to marry a woman of high rank or great estate, if not both, and offended with the ill-disguised hint, Mrs. Dashwood indignantly resolves to remove her residence as quickly as possible. Although Edward is attentive to Elinor, his reserved behaviour makes it difficult for her to guess his intentions. Elinor does not encourage her relatives to hope for the marriage, although in her heart of hearts she secretly hopes for it.

One of Mrs. Dashwood's cousins, the wealthy Sir John Middleton, offers her a cottage on his Devonshire estate, Barton Park, and Mrs. Dashwood decides to accept. She and the girls find it tiny and dark compared to Norland, but try to make the best of it. They are warmly received by Sir John, who insists that they dine with him and his wife frequently at the great house of Barton Park and join the social life of his family. Also staying with Sir John and his reserved and insipid wife is his mother-in-law Mrs. Jennings, a rich and rather vulgar widow who is full of kindness and good humour and who immediately assigns herself the project of finding husbands for the Dashwood girls.

While visiting Sir John, the Dashwoods meet his old friend, the grave, quiet, but gentlemanly Colonel Brandon. It soon becomes apparent that Brandon is attracted to Marianne, and Mrs. Jennings teases them about it. Marianne is not pleased as she considers Colonel Brandon, at age 35, to be an old bachelor incapable of falling in love or inspiring love in anyone else.

Marianne, out for a walk, gets caught in the rain, slips, and sprains her ankle. The dashing, handsome John Willoughby, who is visiting his wealthy aunt, Mrs. Smith, in the area, happens to be out with his gun and friends hunting nearby and sees the accident. He carries Marianne home and soon wins her admiration with his good looks, romantic personality, and outspoken views on poetry, music and art. Willoughby appears the exact opposite of the quiet and reserved Brandon. He visits Marianne every day, and Elinor and Mrs. Dashwood begin to suspect that the couple are secretly engaged. Elinor is worried about Marianne's unguarded conduct in Willoughby's presence and cautions her, but Marianne refuses to check her emotions, believing this to be a falsehood. At a picnic outing, Willoughby and Marianne go off together to see the house and estate that Willoughby is to inherit. Elinor is greatly alarmed by Marianne's going off alone to visit a house, the owner of which - Mrs Smith - is unknown to her. Marianne is angry at Elinor's interference; Elinor assumes (as does Marianne) that Willoughby is showing Marianne the house of which she will be mistress upon their marriage. The next day Mrs Dashwood and Elinor find Marianne in hysterics after a morning visit by Willoughby; he informs them that his aunt is sending him to London on business and that he will not return to their area for as long as a year; he brushes aside an invitation to stay with the Dashwoods and leaves hurriedly. Marianne is distraught and feeds her sorrow by playing the music Willoughby brought for her and reading the books they enjoyed together.

Edward Ferrars pays the Dashwoods a short visit at Barton Cottage but seems unhappy and out of sorts. Elinor fears that he no longer has feelings for her. However, unlike Marianne, she does not allow anyone to see her wallow in her sadness, feeling it her duty to be outwardly calm for the sake of her mother and sisters, who dote on Edward and have firm faith in his love for Elinor.

Anne and Lucy Steele, rather vulgar and uneducated cousins of Lady Middleton, come to stay at Barton Park. Sir John tells Lucy as a joke that Elinor is attached to Edward, prompting Lucy to inform Elinor of her secret four year long engagement to Edward. Although Elinor initially blames Edward for engaging her affections when he was not free to do so, she realizes he became engaged to Lucy while he was young and naïve and perhaps has made a mistake. She thinks or hopes that Edward does not love Lucy, but he will not hurt or dishonour her by breaking their engagement. Elinor hides her disappointment and works to convince Lucy she feels nothing for Edward. This is particularly hard as she sees Lucy may not be sincerely in love with Edward and may only make him unhappy. Lucy tells Elinor that Mrs Ferrars will almost certainly disapprove of the match and that the couple plan to wait until she has died before marrying, unless Edward can find a way of supporting himself financially without her.

Elinor and Marianne spend the winter at Mrs. Jennings' home in London. Marianne writes a series of letters to Willoughby - prompting Elinor to believe that they are indeed engaged, as only engaged couples could properly correspond in this way. However, Marianne's letters go unanswered, and he snubs her coldly when he sees her at a ball. He later writes to Marianne, enclosing their former correspondence and love tokens, including a lock of her hair and informing her of his engagement to a Miss Grey, a high-born, wealthy woman with £50,000 (equivalent to about £1.7 million today)[1]. Marianne is devastated, and admits to Elinor that she and Willoughby were never engaged, but she loved him and he led her to believe he loved her.

Meanwhile, the truth about Willoughby's real character starts to emerge; Colonel Brandon tells Elinor that Willoughby had seduced Brandon's ward, fifteen-year-old Eliza Williams, and abandoned her when she became pregnant. Brandon was once in love with Miss Williams' mother, a woman who resembled Marianne and whose life was destroyed by an unhappy arranged marriage to the Colonel's brother.

Fanny Dashwood, who is also in London for the season, declines her husband's offer to invite the Dashwood girls to stay with her. Instead, she invites the Misses Steele. Lucy Steele becomes very arrogant and brags to Elinor that Fanny's mother, Mrs. Ferrars, favours her. Indeed Fanny and Mrs. Ferrars seem genuinely fond of Lucy - so much so that Miss Anne Steele decides to tell them of Lucy's engagement to Edward. When Mrs. Ferrars discovers Edward's and Lucy's engagement, she is furious while Fanny throws the Misses Steele out onto the street. Mrs. Ferrars demands that Edward end the engagement on pain of disinheritance. Edward, who believes it would be dishonorable to break off with Lucy, refuses and is disinherited in immediate favour of his brother, Robert. Elinor and Marianne feel sorry for Edward, and think him honourable for remaining engaged to a woman with whom he isn't in love.

Edward plans to become ordained as a parish vicar to earn his living and Colonel Brandon, knowing how lives can be ruined when love is denied, expresses his commiseration for Edward's deplorable circumstance to Elinor asking her to be his intermediary in offering Edward a parsonage on Brandon's estate at Delaford, with two hundred pounds a year. Colonel Brandon does not intend the living to enable Edward to marry Lucy as it would be insufficient to pay for a wife and family but intends it to provide Edward some sustenance until he can find something better. Elinor meets Edward's foppish brother Robert and is shocked he has no qualms about claiming his brother's inheritance.

The sisters end their winter stay in London and begin their return trip to Barton via Cleveland, the country estate of Mrs.Jennings' son-in-law, Mr. Palmer. There, miserable over Willoughby, Marianne neglects her health and becomes dangerously ill. Hearing of her serious illness, Willoughby arrives suddenly and reveals to Elinor that he truly loved Marianne, but since he was disinherited when his benefactress discovered his seduction of Miss Williams, he decided to marry the wealthy Miss Grey.

Elinor tells Marianne about Willoughby's visit. Marianne admits that although she loved Willoughby, she could not have been happy with the libertine father of an illegitimate child, even if he had stood by her. Marianne also realizes her illness was brought on by her wallowing in her grief, by her excessive sensibility, and had she died, it would have been morally equivalent to suicide. She now resolves to model herself after Elinor's courage and good sense.

The family learns Lucy has married Mr. Ferrars. When Mrs. Dashwood sees how upset Elinor is, she finally realizes how strong Elinor's feelings are for Edward and is sorry she did not pay more attention to her daughter's unhappiness. However, the next day Edward arrives and reveals it was his brother, Robert Ferrars, who married Lucy. He says he was trapped in his engagement to Lucy, "a woman he had long since ceased to love", and she broke the engagement to marry the now-wealthy Robert. Edward asks Elinor to marry him, and she agrees. Edward eventually becomes reconciled with his mother, who gives him ten thousand pounds. He also reconciles with his sister Fanny. Edward and Elinor marry and move into the parsonage at Delaford.

Mr. Willoughby's patroness eventually gives him his inheritance because of his prudent marriage. Willoughby realizes marrying Marianne would have produced the same effect; had he behaved honourably, he could have had love and money.

Over the next two years, Mrs. Dashwood, Marianne, and Margaret spend most of their time at Delaford. Marianne matures and, at the age of nineteen, decides to marry the 37-year-old Colonel. Although initially she found marriage to someone twenty years her senior repulsive, the gratitude and respect she has come to feel for him develop into a very deep love. The Colonel's house is near the parsonage where Elinor and Edward live, so the sisters and their husbands can visit each other often.

Characters

- Henry Dashwood — a wealthy gentleman who dies at the beginning of the story. The terms of his estate prevent him from leaving anything to his second wife and their children. He asks John, his son by his first wife, to look after (meaning ensure the financial security of) his second wife and their three daughters.

- Mrs. Dashwood — the second wife of Henry Dashwood, who is left in difficult financial straits by the death of her husband. She is 40 years old at the beginning of the book. Much like her daughter Marianne, she is very emotive and often makes poor decisions based on emotion rather than reason.

- Elinor Dashwood — the sensible and reserved eldest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Dashwood. She is 19 years old at the beginning of the book. She becomes attached to Edward Ferrars, the brother-in-law of her elder half-brother, John. Always feeling a keen sense of responsibility to her family and friends, she places their welfare and interests above her own, and suppresses her own strong emotions in a way that leads others to think she is indifferent or cold-hearted.

- Marianne Dashwood — the romantically inclined and eagerly expressive second daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Dashwood. She is 16 years old at the beginning of the book. She is the object of the attentions of Colonel Brandon and Mr. Willoughby. She is attracted to young, handsome, romantically spirited Willoughby and does not think much of the older, more reserved Colonel Brandon. Marianne does the most development within the book, learning her sensibilities have been selfish. She decides her conduct should be more like that of her elder sister, Elinor.

- Margaret Dashwood — the youngest daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Dashwood. She is thirteen at the beginning of the book. She is also romantic and good-tempered but not expected to be as clever as her sisters when she grows older.

- John Dashwood — the son of Henry Dashwood by his first wife. He intends to do well by his half-sisters, but he has a keen sense of avarice, and is easily swayed by his wife.

- Fanny Dashwood — the wife of John Dashwood, and sister to Edward and Robert Ferrars. She is vain, selfish, and snobbish. She spoils her son Harry. Very harsh to her husband's half-sisters and stepmother, especially since she fears her brother Edward is attached to Elinor.

- Sir John Middleton — a distant relative of Mrs. Dashwood who, after the death of Henry Dashwood, invites her and her three daughters to live in a cottage on his property. Described as a wealthy, sporting man who served in the army with Colonel Brandon, he is very affable and keen to throw frequent parties, picnics, and other social gatherings to bring together the young people of their village. He and his mother-in-law, Mrs. Jennings, make a jolly, teasing, and gossipy pair.

- Lady Middleton — the genteel, but reserved wife of Sir John Middleton, she is quieter than her husband, and is primarily concerned with mothering her four spoiled children.

- Mrs. Jennings — mother to Lady Middleton and Charlotte Palmer. A widow who has married off all her children, she spends most of her time visiting her daughters and their families, especially the Middletons. She and her son-in-law, Sir John Middleton, take an active interest in the romantic affairs of the young people around them and seek to encourage suitable matches, often to the particular chagrin of Elinor and Marianne.

- Edward Ferrars — the elder of Fanny Dashwood's two brothers. He forms an attachment to Elinor Dashwood. Years before meeting the Dashwoods, Ferrars proposed to Lucy Steele, the niece of his tutor. The engagement has been kept secret owing to the expectation that Ferrars' family would object to his marrying Miss Steele. He is disowned by his mother on discovery of the engagement after refusing to give up the engagement.

- Robert Ferrars — the younger brother of Edward Ferrars and Fanny Dashwood, he is most concerned about status, fashion, and his new barouche. He subsequently marries Miss Lucy Steele after Edward is disowned.

- Mrs. Ferrars — Fanny Dashwood and Edward and Robert Ferrars' mother. A bad-tempered, unsympathetic woman who embodies all the foibles demonstrated in Fanny and Robert's characteristics. She is determined that her sons should marry well.

- Colonel Brandon — a close friend of Sir John Middleton. In his youth, Brandon had fallen in love with his father's ward, but was prevented by his family from marrying her because his father was determined to marry her to his older brother. He was sent into the military abroad to be away from her, and while gone, the girl suffered numerous misfortunes partly as a consequence of her unhappy marriage, finally dying penniless and disgraced, and with a natural (i.e., illegitimate) daughter, who becomes the ward of the Colonel. He is 35 years old at the beginning of the book. He falls in love with Marianne at first sight as she reminds him of his father's ward. He is very honorable friend to the Dashwoods, particularly Elinor, and offers Edward Ferrars a living after being disowned by his mother.

- John Willoughby — a philandering nephew of a neighbour of the Middletons, a dashing figure who charms Marianne and shares her artistic and cultural sensibilities. It is generally understood that he is engaged to be married to Marianne by many of their mutual acquaintances.

- Charlotte Palmer — the daughter of Mrs. Jennings and the younger sister of Lady Middleton, Mrs. Palmer is jolly but empty-headed and laughs at inappropriate things, such as her husband's continual rudeness to her and to others.

- Thomas Palmer — the husband of Charlotte Palmer who is running for a seat in Parliament, but is idle and often rude.

- Lucy Steele — a young, distant relation of Mrs. Jennings, who has for some time been secretly engaged to Edward Ferrars. She assiduously cultivates the friendship with Elinor Dashwood and Mrs. John Dashwood. Limited in formal education and financial means, she is nonetheless attractive, clever, manipulative, cunning and scheming.

- Anne/Nancy Steele — Lucy Steele's elder, socially inept, and less clever sister.

- Miss Sophia Grey — a wealthy but malicious heiress whom Mr. Willoughby marries in order to retain his comfortable lifestyle after he is disinherited by his aunt.

- Lord Morton — the father of Miss Morton.

- Miss Morton — a wealthy woman whom Mrs. Ferrars wants her eldest son, Edward, and later Robert, to marry.

- Mr. Pratt — an uncle of Lucy Steele and Edward's tutor.

- Eliza Williams — the ward of Col. Brandon, she is about 15 years old and bore an illegitimate son to John Willoughby. She is the daughter of Elizabeth Williams.

- Elizabeth Williams — the former love interest of Colonel Brandon. Williams is Brandon's father's ward, and is forced to marry Brandon's older brother. The marriage is an unhappy one, and it is revealed that her daughter is left as Colonel Brandon's ward when he finds his lost love dying in a poorhouse.

- Mrs. Smith — the wealthy aunt of Mr. Willoughby who disowns him for not marrying Eliza Williams.

Critical appraisal

Austen wrote the first draft of Elinor and Marianne (later retitled Sense and Sensibility) in epistolary form sometime around 1795 when she was about 19 years old. While she had written a great deal of short fiction in her teens, Elinor and Marianne was her first full-length novel. The plot revolves around a contrast between Elinor's sense and Marianne's emotionalism; the two sisters may have been loosely based on the author and her beloved elder sister, Cassandra, with Austen casting Cassandra as the restrained and well-judging sister and herself as the emotional one.

Austen clearly intended to vindicate Elinor's sense and self-restraint, and on the simplest level, the novel may be read as a parody of the full-blown romanticism and sensibility that was fashionable around the 1790s. Yet Austen's treatment of the two sisters is complex and multi-faceted. Austen biographer Claire Tomalin argues that Sense and Sensibility has a "wobble in its approach", which developed because Austen, in the course of writing the novel, gradually became less certain about whether sense or sensibility should triumph.[2] She endows Marianne with every attractive quality: intelligence, musical talent, frankness, and the capacity to love deeply. She also acknowledges that Willoughby, with all his faults, continues to love and, in some measure, appreciate Marianne. For these reasons, some readers find Marianne's ultimate marriage to Colonel Brandon an unsatisfactory ending.[3] The ending does, however, neatly join the themes of sense and sensibility by having the sensible sister marry her true love after long, romantic obstacles to their union, while the emotional sister finds happiness with a man whom she did not initially love, but who was an eminently sensible and satisfying choice of a husband.

The novel displays Austen's subtle irony at its best, with many outstanding comic passages about the Middletons, the Palmers, Mrs. Jennings, and Lucy Steele.

Publication

In 1811, Thomas Egerton of the Military Library publishing house in London accepted the manuscript for publication, in three volumes. Austen paid for the book to be published and paid the publisher a commission on sales. The cost of publication was more than a third of Austen's annual household income of £460 (about £15,282 in 2008 currency)[4]. She made a profit of £140 (£4,754.40 in 2008 currency[5]) on the first edition, which sold all 750 printed copies by July 1813. A second edition was advertised in October 1813.

Editions

- Sense & Sensibility, Oneworld Classics 2008 ISBN 978-1-84749-046-9

- Sense & Sensibility, Oxford University Press 2004 ISBN 978-0192833426

- Sense & Sensibility, Penguin Classics 2003, ISBN 978-0141439662

- Sense & Sensibility, Collectors Library 2003, ISBN 978-1-904633-02-0

See also

- Sense and Sensibility (1981 TV serial)

- Sense and Sensibility (film) starring Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet

- Kandukondain Kandukondain (2000 film) a modern Tamil adaptation starring Tabu, Aishwarya Rai, Ajith and Mammootty.

- Sense and Sensibility (2008 TV serial), BBC serial starring Hattie Morahan and Charity Wakefield

- Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters (2009): parody pastiche—in this case, a mashup—novel authored by Ben Winters. A mashup novel appropriates text and the author's name from an original source that is no longer protected by copyright, integrating new narrative into the original to create a new (mashup) story on the back of the original. Typically, the mashup story is a sendup of the original story. Also typical, the mashup publisher prints the original author's name in a manner that falsely represents the original author as a collaborator, or even as a joint author of the mashup novel.

References

- ↑ The National Archives "Take a Break: Currency Converter". http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/default0.asp

- ↑ Claire Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life (New York: Vintage, 1997), p.155.

- ↑ Tomalin, Jane Austen: A Life, pp. 156-157.

- ↑ Jane Austen's World. "Pride and Prejudice Economics: Or Why a Single Man with a Fortune of £4,000 Per Year is a Desirable Husband". 10 Feb 2008. http://janeaustensworld.wordpress.com/2008/02/10/the-economics-of-pride-and-prejudice-or-why-a-single-man-with-a-fortune-of-4000-per-year-is-a-desirable-husband/

- ↑ Jane Austen's World

External links

- Sense and Sensibility at Project Gutenberg

- Sense and Sensibility - Full text with audio and translations.

- Sense and Sensibility free downloads in PDF, PDB, and LIT formats

- "Sense and Sensibility the Musical" by Jeffrey Haddow and Neal Hampton

- Sense and Sensibility analysis and resources for teachers and students

- "Novelguide: Sense and Sensibility" Novel Guide for teachers and students

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

_hires.jpg)

.jpg)